60 years ago tonight: The Dresden Firestorm

60 years ago this evening, Dresden was destroyed. It is an event that has had profound political ramifications even today and poses difficult moral questions that I will try to address, because, given my interest in debunking Holocaust denial, Dresden is a topic that all too often comes up, with Holocaust deniers trying to claim a moral equivalence between the Nazis and the Allies. Before these questions can be addressed, however, it is necessary to describe what happened that fiery night and dispose of some of the myths that persist about the bombing. What happened was awful enough without these myths. Indeed, it can be argued that the destruction of Dresden was the result not of any one act, but a consequence of total war.

Dresden had been oddly fortunate up until this date in 1945. While other cities, particularly Berlin and the industrial cities of western Germany, suffered bombing raid after bombing raid and the city of Hamburg had suffered a monumental firestorm a year and a half earlier, as of mid-February 1945, even with the Red Army a mere 75 miles to the east and advancing, somehow Dresden had avoided this fate. True, it had not completely escaped damage. and scares. As early as August 1940, air raid sirens had sounded over the city. It was a false alarm. In October 1940, three high-explosive bombs had actually fallen in a field just southeast of the city. After that, in 1941 there were seven air raid warnings and in 1942, four. Despite the fact that its sister city Leipzig, located a mere 60 miles away, was bombed multiple times during 1943 and 1944, despite having 203 air raid warnings over the course of these two years, in early 1945 Dresden remained largely untouched.

Indeed, this escape from the destruction other cities endured time and time again contributed to a false sense of security among Dresdeners--that, and its location in the far eastern reaches of Germany and its reputation as a cultural center of great beauty of "no military importance." ("Why would anyone want to bomb Dresden?" was a frequent refrain.) This confidence was so great that parents refused to send their children to the countryside for safety, as parents in so many other German cities were being forced to do, leading a rather weak "order" in December 1943 for parents to send their children out of Dresden. This order was was widely ignored, leading to a stronger order in January 1944 warning parents that children who did not go to the countryside would not be entitled to schooling in Dresden. Parents found ingenious ways to get around this order, to the point that official documents spoke with a sense of resignation regarding efforts to relocate the children. In August 24, 1944, the first Allied bombing raid that actually caused casualties within Dresden occurred. The USAAF targeted the Rhenania Ossag hydrogenation works--which made oil used in the Wehrmacht's tanks--in the Dresden suburb of Freital, during a daylight raid. 241 people died. However, little damage occurred in the city of Dresden itself. On October 7, 1944, Dresden was hit again by the USAAF, but only because its Friedrichstadt marshalling yards happened to be a secondary target of a larger raid, to be bombed only in the event that the primary target could not be found. This raid should have caused serious concern, because it was an improvised raid with fewer than 30 American bombers diverted from other targets and it still had resulted in the deaths of 270 people. But it didn't. Most Dresdeners considered the raid an anomaly. The city was subjected to one more raid before the end, a raid that occurred on January 16, 1945. Once again, Dresden was a secondary target, but this time 127 bombers attacked the city, killing 376 people and spreading intermittent areas of destruction over a four mile swath of the city.

At this point, even though it should have been clear that Dresden's "special status" among German cities was an illusion, Dresdeners still clung to this illusion. They did not know that, on January 1, 1945, Colonel General Heinz Guderian, Chief of the Army General Staff, had designated Dresden a military strongpoint, a "defensive area" (Verteidigungbereich). Dresden was to be one of several strongpoints to be used in a last desperate effort to slow the relentless Russian advance into Germany. Even if the citizens had known that their city was in Allies' sites, there was not much that could have been done anyway. By February, the German defenses were utterly collapsing, and the Red Army was rapidly advancing from the East. The air raid equipment and antiaircraft batteries from Dresden had been mostly removed and taken to places where they were more urgently needed. The city was largely defenseless.

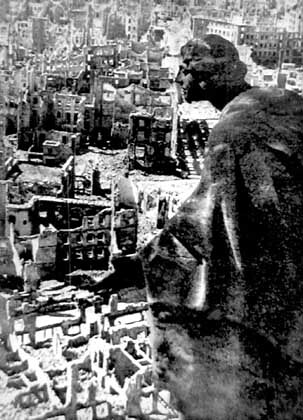

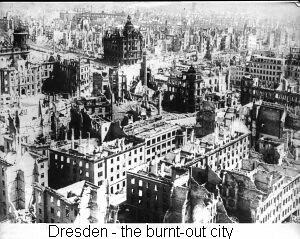

And then, on Tuesday, February 13, 1945, with Hitler's death and war's end less than three months away, Dresden's luck finally ran out. On the night of Shrove Tuesday, in two raids, a total of nearly 800 RAF bombers dropped 2,690 tons of incendiaries and high explosives on the capital of Saxony. 244 Lancaster bombers hit the city center between 10:13 PM and 10:28 PM, pummeling it with 881 tons of bombs, 43% of which were incendiaries. By 11:00 PM, the early stages of the firestorm were becoming evident. But worse was in store. 550 more bombers were on their way, guided to their target by the light of the fires raging in Dresden, which were visible 50-100 miles away. As Bomb aimer Miles Trip, quoted by Frederick Taylor, in his excellent book Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945 described it:

Since the firestorm, several key myths have been repeated and become "common knowledge." Frederick Taylor, while not justifying the Dresden raid, has debunked at least three of them:

In considering the moral questions involved in the Allied bombing campaign, it helps to remember how it was started. The possibility of aerial war was contemplated nearly 40 years earlier and even regulated in the Hague convention, which prohibited attacks on undefended towns and villages. Mainly because the technology didn't exist, there were few such attacks on towns in World War I anyway, other than German zeppelin raids on London and occasional highly ineffectual attempts at bombing. Between the World Wars, there developed a contingent of military men who became fervent believers in the concept that air power alone, specifically strategic bombing, could win wars. In fact, some went so far as to claim that air power would ultimately render ground forces necessary only to move in and take over territory after strategic bombing had defeated the enemy. Thus was born the "bomber's dream," which, boiled down to its essence, is the belief that wars could be won by bombing alone.

Although there were attempts at strategic bombing before, the first serious sustained strategic bombing occurred in 1940. In August 1940, Germany bombed London. The British retaliated with bombing raids on Berlin. This so enraged Hitler that he ordered a massive sustained bombing campaign on Britain, which became known as the "Blitz" or the Battle of Britain. Over 40,000 British civilians were killed in the fall of 1940. The bombing campaign nearly broke the back of the RAF, but somehow Britain held out.

The Blitz probably explains much of why the British were always more enthusiastic for strategic bombing than the Americans. They understandably viewed it as payback, having experienced first hand the horrors of aerial bombing themselves. Nonetheless, when they first started their bomber campaign, they concentrated solely on strategic objectives, such as dockyards, military installations, and munitions factories. However, the accuracy of their bombing was woefully lacking. Indeed, in 1941 an analysis of the effectiveness of British bombing based on 100 separate raids on 28 targets over 48 nights in June and July 1941 observed: Of those aircraft recorded as attacking their target, only one in three got within five miles. Over the French ports, the proportion was two in three. Over Germany as a whole, the proportion was one in four. Over the Ruhr [the heart of industrial Germany] it was only one in ten. Because of the high casualty rates among bomber crews flying unprotected by fighter escorts in the daylight, the British came to favor large night-time raids on cities, while the Americans advocated daylight "precision bombing" raids from very high altitudes against factories and other military targets. However, for both, low accuracy meant relatively low success at destroying the intended target and a high likelihood of "collateral damage." Lack of fighter escort meant very high bomber loss and casualty rates among the crews, so much so that there was concern in 1942 and 1943 that the casualty rates were higher than what could be replaced by training new crews. However, it must also be remembered that, in the early years of the war, the British and Americans really had no other means of engaging Germany in Europe, and political forces were such that British leaders didn't want to be perceived as "doing nothing." Over time, the momentum favoring bombing grew and grew, so that it continued even after Germany was clearly losing. The bomber's dream still drove it, and still lives today (for example, in the war on Kosovo in 1998, in which nearly no ground troops were used until after Serbia surrendered).

So how to answer the Holocaust denier's charge that bombings like those of Hamburg or Dresden (or, in the Pacific, Tokyo and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) were morally equivalent? One answer obviously presents itself. Whatever its results and intent, the bombing campaign was not (at least until late in the war) directed solely or even primarly against defenseless people. Indeed, the high bomber crew casualty rates that caused so much concern about the sustainability of the bombing campaign were due to highly formidable German air defenses. Casualty rates among bomber crews remained very high until well into 1944, when long-range fighter escorts became available. The bombers' intent was not to eliminate an entire race of people from the face of a continent, as the intent of the Holocaust was, but rather to destroy infrastructure and military targets and and to "demoralize" the populace into demanding surrender. (It succeeded at the first aim and almost utterly failed at the second aim.) Second, there was a military rationale for the bombing campaign, in fact a rationale that seemed very compelling to a great many military and civilian commanders at the time, most prominent of which were Winston Churchill and "Bomber" Harris. That the rationale may has been questioned and may have been incorrect is something that we can see now in hindsight but that was not readily apparent 60 years ago, although some did question the wisdom of this campaign. As James Woudhuysen puts it: If, for instance, we search for a military rationale for the Nazis' Holocaust, in which a whole industry had to be built to kill six million Jews, we will search for a long time. Once Germany was engulfed by fascism, all kinds of irrationality were possible. (To that I would add: In fact, the Holocaust actually decreased Germany's war-fighting ability, as the personnel and enormous resources retained late in the war for maintaining the camps for killing Jews could certainly have been better used to defend Germany.) In addition, as Frederick Taylor points out: It is rarely mentioned that almost exactly the same number of Soviet citizens died as a result of [German] bombing during the Second World War as Germans: around half a million. However, it is still clear that the Allied bombing campaign against cities, both in Germany and Japan, is perhaps the single most morally difficult question that is asked about the conduct of the war by the Allies. Once the relentless logic of total war takes hold, it allows the justification of things we would normally consider abhorrent and may consider abhorrent later. I am not sure that there is an good answer to this question, but I emphatically point out that, whatever other things the bombing campaign may have been, it was not morally equivalent to the Holocaust. Another thing I do know is that claiming moral equivalency of the Allied bombing campaign to the Holocaust will not justify the Holocaust or diminish its horror. World War II was the bloodiest war in history, and, as the distance of time allows more perspective, I hope that we will be able to use what we have learned to try to prevent anything like it from ever happening again. If that sounds like a copout, it probably is to some extent. But it's also about as close as I can come to the truth right now.

(Note: Other articles are here, here, here, here, and here.)

Dresden had been oddly fortunate up until this date in 1945. While other cities, particularly Berlin and the industrial cities of western Germany, suffered bombing raid after bombing raid and the city of Hamburg had suffered a monumental firestorm a year and a half earlier, as of mid-February 1945, even with the Red Army a mere 75 miles to the east and advancing, somehow Dresden had avoided this fate. True, it had not completely escaped damage. and scares. As early as August 1940, air raid sirens had sounded over the city. It was a false alarm. In October 1940, three high-explosive bombs had actually fallen in a field just southeast of the city. After that, in 1941 there were seven air raid warnings and in 1942, four. Despite the fact that its sister city Leipzig, located a mere 60 miles away, was bombed multiple times during 1943 and 1944, despite having 203 air raid warnings over the course of these two years, in early 1945 Dresden remained largely untouched.

Indeed, this escape from the destruction other cities endured time and time again contributed to a false sense of security among Dresdeners--that, and its location in the far eastern reaches of Germany and its reputation as a cultural center of great beauty of "no military importance." ("Why would anyone want to bomb Dresden?" was a frequent refrain.) This confidence was so great that parents refused to send their children to the countryside for safety, as parents in so many other German cities were being forced to do, leading a rather weak "order" in December 1943 for parents to send their children out of Dresden. This order was was widely ignored, leading to a stronger order in January 1944 warning parents that children who did not go to the countryside would not be entitled to schooling in Dresden. Parents found ingenious ways to get around this order, to the point that official documents spoke with a sense of resignation regarding efforts to relocate the children. In August 24, 1944, the first Allied bombing raid that actually caused casualties within Dresden occurred. The USAAF targeted the Rhenania Ossag hydrogenation works--which made oil used in the Wehrmacht's tanks--in the Dresden suburb of Freital, during a daylight raid. 241 people died. However, little damage occurred in the city of Dresden itself. On October 7, 1944, Dresden was hit again by the USAAF, but only because its Friedrichstadt marshalling yards happened to be a secondary target of a larger raid, to be bombed only in the event that the primary target could not be found. This raid should have caused serious concern, because it was an improvised raid with fewer than 30 American bombers diverted from other targets and it still had resulted in the deaths of 270 people. But it didn't. Most Dresdeners considered the raid an anomaly. The city was subjected to one more raid before the end, a raid that occurred on January 16, 1945. Once again, Dresden was a secondary target, but this time 127 bombers attacked the city, killing 376 people and spreading intermittent areas of destruction over a four mile swath of the city.

At this point, even though it should have been clear that Dresden's "special status" among German cities was an illusion, Dresdeners still clung to this illusion. They did not know that, on January 1, 1945, Colonel General Heinz Guderian, Chief of the Army General Staff, had designated Dresden a military strongpoint, a "defensive area" (Verteidigungbereich). Dresden was to be one of several strongpoints to be used in a last desperate effort to slow the relentless Russian advance into Germany. Even if the citizens had known that their city was in Allies' sites, there was not much that could have been done anyway. By February, the German defenses were utterly collapsing, and the Red Army was rapidly advancing from the East. The air raid equipment and antiaircraft batteries from Dresden had been mostly removed and taken to places where they were more urgently needed. The city was largely defenseless.

And then, on Tuesday, February 13, 1945, with Hitler's death and war's end less than three months away, Dresden's luck finally ran out. On the night of Shrove Tuesday, in two raids, a total of nearly 800 RAF bombers dropped 2,690 tons of incendiaries and high explosives on the capital of Saxony. 244 Lancaster bombers hit the city center between 10:13 PM and 10:28 PM, pummeling it with 881 tons of bombs, 43% of which were incendiaries. By 11:00 PM, the early stages of the firestorm were becoming evident. But worse was in store. 550 more bombers were on their way, guided to their target by the light of the fires raging in Dresden, which were visible 50-100 miles away. As Bomb aimer Miles Trip, quoted by Frederick Taylor, in his excellent book Dresden: Tuesday, February 13, 1945 described it:

Although we were forty miles from Dresden, fires were reddening the sky ahead. The meteorologic forecasts had been correct. There was no cloud over the city.From 1:20 to 1:45 AM, Wednesday, February 14 (Ash Wednesday, appropriately enough), the remaining bombers dropped their deadly cargo on the city. By the time they were through, Dresden, the victim of perfect weather, no air defenses, bombing far more accurate than the crude methods of World War II usually produced, and the most horrible of luck, had been engulfed by the rarest of things: The perfect firestorm. Victor Klemperer, one of the few Jews to have survived in Dresden through the entire war (mainly because he was married to an "Aryan") and whose memoir, I Will Bear Witness, is an indespensible account of the gradually increasing persecution of Jews by the Nazis that culminated in the Holocaust observed:

Six miles from the target, other Lancasters were clearly visible; their silhouettes black in the rosy glow. The streets of the city were a fantastic latticework of fire. It was as though one was looking down at the fiery outlines of a crossword puzzle; blaxing streets stretched from east to west, from north to south, in a giagantic saturation of flame. I was completely awed by the spectacle.

Within a wider radius, nothing but fires. Standing out like a torch on this side of the Elbe, the tall building at Pirnaischer Platz, glowing white; as bright as day on the other side, the roof of the Finance Ministry...the storm again and again tore at my blanket, hurt my head.Dresden suffered one more punishment that day. The USAAF followed up with a previously planned followup daylight raid in the early afternoon of February 14. The fires burned for more than a week, and an estimated 35,000 people died, many in the air raid shelters, from which the firestorm sucked the oxygen. Many died in the boiling waters of fountains in the mistaken belief that the water would protect them. It didn't. It boiled away.

Since the firestorm, several key myths have been repeated and become "common knowledge." Frederick Taylor, while not justifying the Dresden raid, has debunked at least three of them:

- Inflated death tolls. Death tolls were inflated for propaganda purposes at the behest of Josef Goebbels. These "estimates" ranged to as high as 250,000 (and even 300,000+) people. Noted Holocaust denier and self-proclaimed historian David Irving touted an estimate of 100,000. However, the most recent research on the topic suggests that the toll was between 25,000 and 40,000, horrible enough without exaggeration.

- Dresden was a city of "no military importance." This is also untrue, at least by the standards of the time. There were a large number of precision engineering companies headquartered in Dresden, many of which made instruments for the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe. Zeiss-Ikon manufactured precision optics in Dresden, much of which went in the later years of the war to sights for antiaircraft batteries. There was the previously mentioned hydrogenation plant. Many of these plants used Jewish slave labor in the later years of the war, when worker shortages were accute. Next, Dresden was an important rail transportation hub for all of Saxony and eastern Germany. Finally, there were a number of military barracks in and around the city. By any criteria used at the time, Dresden was a legitimate military target.

- Allied planes strafed survivors fleeing the city. There is no evidence that this happened. In fact, it would have been irresponsible, because the escort fighters were operating close to the limit of their range, and undertaking strafing runs would have used fuel they could ill afford. There were some strafing runs far to the west of Dresden, but against railroad targets. Also, there was a brief low-level dogfight near and over the city, which may have contributed to such stories. To people on the ground, they may have appeared to be strafing and it is possible that some civilians may even have been hit by the fire.

In considering the moral questions involved in the Allied bombing campaign, it helps to remember how it was started. The possibility of aerial war was contemplated nearly 40 years earlier and even regulated in the Hague convention, which prohibited attacks on undefended towns and villages. Mainly because the technology didn't exist, there were few such attacks on towns in World War I anyway, other than German zeppelin raids on London and occasional highly ineffectual attempts at bombing. Between the World Wars, there developed a contingent of military men who became fervent believers in the concept that air power alone, specifically strategic bombing, could win wars. In fact, some went so far as to claim that air power would ultimately render ground forces necessary only to move in and take over territory after strategic bombing had defeated the enemy. Thus was born the "bomber's dream," which, boiled down to its essence, is the belief that wars could be won by bombing alone.

Although there were attempts at strategic bombing before, the first serious sustained strategic bombing occurred in 1940. In August 1940, Germany bombed London. The British retaliated with bombing raids on Berlin. This so enraged Hitler that he ordered a massive sustained bombing campaign on Britain, which became known as the "Blitz" or the Battle of Britain. Over 40,000 British civilians were killed in the fall of 1940. The bombing campaign nearly broke the back of the RAF, but somehow Britain held out.

The Blitz probably explains much of why the British were always more enthusiastic for strategic bombing than the Americans. They understandably viewed it as payback, having experienced first hand the horrors of aerial bombing themselves. Nonetheless, when they first started their bomber campaign, they concentrated solely on strategic objectives, such as dockyards, military installations, and munitions factories. However, the accuracy of their bombing was woefully lacking. Indeed, in 1941 an analysis of the effectiveness of British bombing based on 100 separate raids on 28 targets over 48 nights in June and July 1941 observed: Of those aircraft recorded as attacking their target, only one in three got within five miles. Over the French ports, the proportion was two in three. Over Germany as a whole, the proportion was one in four. Over the Ruhr [the heart of industrial Germany] it was only one in ten. Because of the high casualty rates among bomber crews flying unprotected by fighter escorts in the daylight, the British came to favor large night-time raids on cities, while the Americans advocated daylight "precision bombing" raids from very high altitudes against factories and other military targets. However, for both, low accuracy meant relatively low success at destroying the intended target and a high likelihood of "collateral damage." Lack of fighter escort meant very high bomber loss and casualty rates among the crews, so much so that there was concern in 1942 and 1943 that the casualty rates were higher than what could be replaced by training new crews. However, it must also be remembered that, in the early years of the war, the British and Americans really had no other means of engaging Germany in Europe, and political forces were such that British leaders didn't want to be perceived as "doing nothing." Over time, the momentum favoring bombing grew and grew, so that it continued even after Germany was clearly losing. The bomber's dream still drove it, and still lives today (for example, in the war on Kosovo in 1998, in which nearly no ground troops were used until after Serbia surrendered).

So how to answer the Holocaust denier's charge that bombings like those of Hamburg or Dresden (or, in the Pacific, Tokyo and the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki) were morally equivalent? One answer obviously presents itself. Whatever its results and intent, the bombing campaign was not (at least until late in the war) directed solely or even primarly against defenseless people. Indeed, the high bomber crew casualty rates that caused so much concern about the sustainability of the bombing campaign were due to highly formidable German air defenses. Casualty rates among bomber crews remained very high until well into 1944, when long-range fighter escorts became available. The bombers' intent was not to eliminate an entire race of people from the face of a continent, as the intent of the Holocaust was, but rather to destroy infrastructure and military targets and and to "demoralize" the populace into demanding surrender. (It succeeded at the first aim and almost utterly failed at the second aim.) Second, there was a military rationale for the bombing campaign, in fact a rationale that seemed very compelling to a great many military and civilian commanders at the time, most prominent of which were Winston Churchill and "Bomber" Harris. That the rationale may has been questioned and may have been incorrect is something that we can see now in hindsight but that was not readily apparent 60 years ago, although some did question the wisdom of this campaign. As James Woudhuysen puts it: If, for instance, we search for a military rationale for the Nazis' Holocaust, in which a whole industry had to be built to kill six million Jews, we will search for a long time. Once Germany was engulfed by fascism, all kinds of irrationality were possible. (To that I would add: In fact, the Holocaust actually decreased Germany's war-fighting ability, as the personnel and enormous resources retained late in the war for maintaining the camps for killing Jews could certainly have been better used to defend Germany.) In addition, as Frederick Taylor points out: It is rarely mentioned that almost exactly the same number of Soviet citizens died as a result of [German] bombing during the Second World War as Germans: around half a million. However, it is still clear that the Allied bombing campaign against cities, both in Germany and Japan, is perhaps the single most morally difficult question that is asked about the conduct of the war by the Allies. Once the relentless logic of total war takes hold, it allows the justification of things we would normally consider abhorrent and may consider abhorrent later. I am not sure that there is an good answer to this question, but I emphatically point out that, whatever other things the bombing campaign may have been, it was not morally equivalent to the Holocaust. Another thing I do know is that claiming moral equivalency of the Allied bombing campaign to the Holocaust will not justify the Holocaust or diminish its horror. World War II was the bloodiest war in history, and, as the distance of time allows more perspective, I hope that we will be able to use what we have learned to try to prevent anything like it from ever happening again. If that sounds like a copout, it probably is to some extent. But it's also about as close as I can come to the truth right now.

(Note: Other articles are here, here, here, here, and here.)

i consider the question of moral equivalence irrelevant. of course, i also consider holocaust deniers irrelevant. when you have situations like dresden or hiroshima or the turning of blind eyes, it's hard to find any ground on which to speak of morality. sure, we can talk of varying degrees of hideous human suffering and the corresponding reasons, but i think therein lies one of the biggest dangers. the real underlying propaganda that all people want to believe is that they are better, facilitated when presented with an "other" to hate. any justifications of actions resulting in the deaths of countless innocents is opening an apologetic door to fascism.

ReplyDelete-ali(somewhere in there i meant to applaud you for the detail of your post. i hope my tone wasn't too combative, because it wasn't meant to be.)

thanks for the history lesson!

ReplyDeleteGreat read:

ReplyDeleteDo you know why the bombing continued in light of the fact that, as you describe it, the city was already up in flames and most probably on the brink of complete destruction was there a reason to continue the bombing?

has there ever been a bombing terminated early?

Great post!

ReplyDeleteI agree with the first commenter. To "defend" the Nazi Holocaust by pointing out the morally questionable actions of the allies is a fallacy of thought and a seriously flawed comparison.

The allies bombed strategic sites in enemy territory with the ability but not the clear intent to cause mass civilian causalities.

The Nazis built up an entire industry with the clear intent of exterminating millions of their OWN citizens for nothing other than the fact that they were Jews.

With the A-Bomb attacks in Japan, the clear intent by the U.S. was to attack a civilian target and cause mass civilian causalities However, ironically the larger goal of these attacks was to literally force the Japanese government to end the war thus saving literally millions of American and Japanese lives and the whole of the Japanese civilization.

From a moral standpoint both the Dresden and the Japan bombings can be seen as morally justified using utilitarian ethics. It needed to happen to protect the greater good and this was the clear intent.

On the other hand, there is no moral justification for the intentional mass murder of your own citizens based on religious criteria.

Slaughterhouse Five was also my first association, as the only source of any info I ever had on Dresden bombing...that is until today. Thanks.

ReplyDeletePoo-tee-weet!

Good post, although I think you're a little off on a few of the more military matters.

ReplyDeleteThe Battle of Britain began as an attack on the channel convoys, then came to focus on destroying the RAF in order to clear the way for the eventual invasion of southern England. This was the initial objective, only re-directed by Hitler into the 'Blitz', or bombing campaign against British cities like London and Conventry. It was this fatal redirection from attacks on RAF Fighter Command to the major population centers that delayed indefinitely the invasion.

As for the objectives of the strategic bombing campaign, the USAAF and RAF came at it from distinctly different perspectives. Initially directed against Kriegsmarine targets (due to pressure from the Royal Navy, especially during the Phony War), after the fall of France and the initial attack on Berlin the British began bombing population centers in hope that there would be a complete collapse of the German civil morale, much as Giulio Douhet had proposed nearly 20 years before.

The USAAF was hoping to find weak points in the German wartime economy, in what became the Center of Gravity theory of strategic bombardment. There hope was to target certain industries, which would logistically criple the Wehrmacht and Luftwaffe. The result was the oil campaign, targetting Romanian oilfields like Ploesti as well as German synthetic POL facilities. Then there was the ball-bearing campaign, which sought to destroy the entirety of Germany's concentrated ball-bearing manufacturers. Unfortunately for the USAAF, these campaign were failures, if only due to the inability of contemporary technology to match up to the military objectives, as well as the German ability to rebuild and redistribute industry following raids.

I think it is a sign of the technological necessities of the time that eventually Douhet was vindicated by the USAAF, when they gained the ability to lay waste of Japan from end to end with B-29 incendiary raids, and ultimately, the nuclear bomb.

Despite my few criticisms, I think you've written an excellent article!

Again, an excellent article.

ReplyDeletethanks for the resource, Orac.

ReplyDeleteToday I was the mug elected to post a refutation of a really OTT Dresden claim on this comments thread in the Sydney Morning Herald's so-called people's blog Webdiary - a really fantastic resource lately for AiG and bidding high to deliver some of the silliest "alternative" and anti-science commentary around.

This is a pity because it is also the centre of some very powerful agitation against the excesses of the incumbent Federal Government.

Anyway, for the really really really exaggerated Dresden dead numbers, Scroll up to the post signed by Karl Kilian.

I'm so pleased I'd kept this article of yours bookmarked for just this kind of quick reference.

May we never forget the cause, and result, Teach our children so they can learn, Brilliant reading. Thanks for the time and trouble.

ReplyDelete